My Twenty Favourite Films (Part 1)

With and without my movie critic cap on

As a fifteen-year-old in the late 1990s, I discovered the website filmsite.org, in which Tim Dirks introduced his top 100 films and much more about the history of cinema. Dirks could certainly not be accused of recency bias, as the initial list contained only one film from the 1990s and three from the 80s. Most of his choices also appeared on the American Film Institute’s top 100 list, released in 1998.

The top five on that list were ‘Citizen Kane’ (1941), ‘Casablanca’ (1942), ‘The Godfather’ (1972), ‘Gone with the Wind’ (1939), and ‘Lawrence of Arabia’ (1962). I devoured all of them on VHS, and wasn’t just being a pretentious teenager when I said I found them engrossing.

A fascination with classic films gave me something to dream about as an inmate of an all-boy’s faith school. In 2000, I escaped the school and started a Film Studies A-Level. On that course, I was assigned to write about many of the films that were on Dirks’ list, including ‘Double Indemnity’ (1944) and ‘Bonnie and Clyde’ (1967). This was the teenage equivalent of being paid for what you love.

I also got acquainted with ‘world cinema’. Foreign-language films that often appear near the top of critics all-time lists include ‘Tokyo Story’ (1953), in which very little happens but the director masterfully evokes the emotions the characters are conditioned not to show, and ‘The Rules of the Game’ (1939). They say of the latter that if France had been wiped out during World War 2 and nothing survived but a copy of that film, they could have used it to rebuild French society from scratch.

The above-mentioned films all deserve their reputations as classics. But they are not necessarily films one could enjoy while completely switched off. Here is part one of my all-time top 20 films that you will love with or without your high brow cinephile hat on.

All About Eve (1950)

The 1950s is the most represented decade both on Tim Dirks’ list and the American Film Institute’s top 100. There were multiple films from that period which, because of the sheer depth and quality of the writing, acting, and other aspects of storytelling, were impossible not to include.

These included ‘On the Waterfront’, ‘Twelve Angry Men’, ‘From Here to Eternity’, and ‘The Sweet Smell of Success’. But for this much smaller list, I have gone with backstage comedy drama ‘All about Eve’. Ageing theatre actress Margo Channing (Bette Davies) takes in cringey super-fan Eve Harrington (Anne Baxter) as an assistant.

It gradually emerges that Eve is not the ‘starry-eyed idealist’ she appears to be. Her attempts to usurp Margot’s career and another woman’s husband would make most gangsters blush. Everyone involved is in the form of their career, and most people’s favourite character is critic Adison DeWitt, for whom the sardonic cynic George Sanders is perfectly cast.

Amadeus (1984)

This is a film about artistic greatness and the unfairness of how it is achieved. Schoolboy Antonio Salieri prays that he will grow up to be a great composer, offering God his piety and obedience, only to find that greatness has been granted to the ‘boastful, lustful, smutty’ Mozart.

Salieri becomes a vengeful monster who sets out to destroy Mozart, but emerges as the more tragic and sympathetic character. The final 25 minutes, which involves Salieri and Mozart composing a Requiem Mass together, is breathless.

The Apartment (1960)

In this romantic comedy, timid office worker Bud Baxter (Jack Lemmon) climbs the greasy pole at his insurance company by allowing superiors to use his apartment to cheat on their wives. That is until he develops feelings for a colleague and learns to stand up for himself.

Other comedies that didn’t quite make this list – Airplane, even Some Like It Hot, which came from the same director and star– have far more laugh-out-loud moments. But this portrays an unpleasant aspect of American society while never ceasing to be charming.

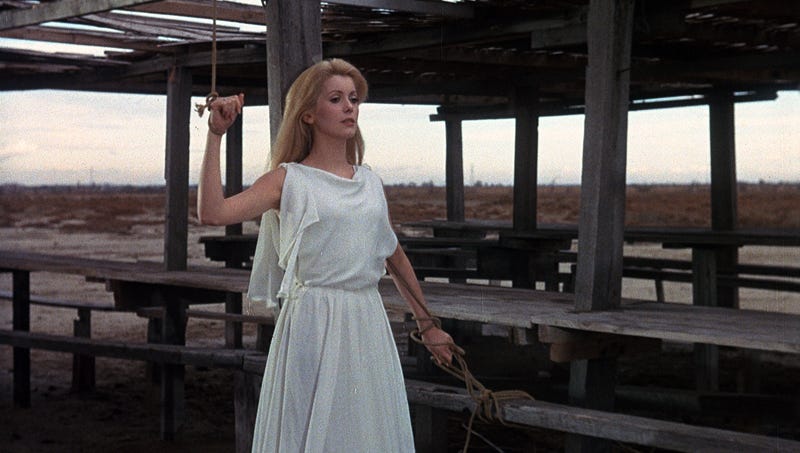

Belle de Jour (1967)

Spaniard Luis Buñuel was one of the great filmmakers. Starting in the 1920s with dream-like masterpiece ‘Un Chien Andalou’, which he made with Salvador Dali, Buñuel spent most of his life in exile from Francoist Spain.

He peaked while based in France in the 1960s, and his most commercially successful film was ‘Belle de Jour’. In it, bored housewife Catherine Deneuve becomes a prostitute to pass the time. It contains all of Buñuel’s signature touches, skewering of middle-class values and the Catholic church and blurred boundaries between dreams and reality.

Cabaret (1972)

This is a musical that even people who hate musicals will adore. In 1931, protagonist Sally Bowles (Liza Minelli) is a singer at the Kit Kat Club in Berlin, a hive of debauchery in a doomed society.

Sally gets into a love triangle with an English teacher and a baron, which provides a backdrop to her performances at the club, where her songs (each one a banger) reflect what is going on in the story. The Nazi Party looms ominously, and the main characters (Jews, homosexuals, eccentrics, and intellectuals) are surely all headed for the slaughter.

Chinatown (1974)

Often described as the greatest screenplay ever written, ‘Chinatown’ has a labyrinthine plot and a gut-wrenching ending. Director Roman Polanski and stars Jack Nicholson and Faye Dunaway already had masterpieces under their belt and were at the peak of their powers.

John Huston, who is best remembered as a director, plays a wealthy industrialist whose evil genius becomes increasingly apparent as the story unfolds. In ‘Story: Substance, Structure, Style, and the Principles of Screenwriting’, Robert McKee cites the climax as the ultimate example of writing from the inside-out.

The Godfather (1972)/ The Godfather 2 (1974)

The head of a large organisation has three sons. Michael, the youngest is the most reluctant to enter the family business, but ends up running it. The business is organised crime.

In the sequel, which is even more ambitious because it is also a prequel, we learn of the godfather’s origin story and see what happens to the family business under Michael. The BBC wrote of it: “Fifty years on from its release in March 1972, it stands as the defining US artwork not just on organised crime, but on immigration, capitalism and corruption.”

Goodfellas (1990)

Whereas The Godfather portrays the criminal underworld as honourable, and even gentlemanly, ‘Goodfellas’ is about gang members who are obnoxious loudmouths and amoral sociopaths.

Based on the 1985 biography ‘Wiseguy: Life in a Mafia Family’ about gangster turned informant Henry Hill, it leaves a lot out. For example, Paul Vario (portrayed as Paul Cicero by Paul Sorvino) had an affair with Hill’s wife that is not shown in the movie. However, Hill and his associates are so brazen, the dialogue so snappy and the soundtrack so zeitgeisty, it is impossible not to get invested.

It is structurally the same as two later Scorsese movies, ‘The Wolf of Wall Street’ and ‘The Irishman’, in that it involves a mild-mannered outsider entering a certain walk of life and then rising and falling within it. It is better than the former because the characters are more relatable, and better than the latter because of superior pacing.

Jaws (1975)

Directed by Steven Spielberg when in his mid-twenties, ‘Jaws’ was the original summer blockbuster. From the dynamic between the three leads to John Williams’ masterfully understated score, it is as gripping as it was all those decades ago.

Famously, the real reason why the shark does not appear for over an hour is because the artificial shark was late in being delivered. What was thought to be minimalistic decision-making was actually just a necessity. That’s the thing about great art – it must be necessary.

Kind Hearts and Coronets (1949)

The 1940s was a period of great filmmaking in Britain. As well as the films of Powell and Pressburger, and the early career of David Lean, there were the Ealing comedies. These mixed unflinching social realism with stoic charm. They included wacky heists ‘The Lavender Hill Mob’ and ‘The Ladykillers’ and ones that thumbed their noses at the establishment, like ‘Whiskey Galore’ and ‘The Man in the White Suit’.

The greatest achievement of Ealing was ‘Kind Hearts and Coronets’. With his mother having been banished from an aristocratic family for marrying a foreigner, Louis D’Ascoyne (Denis Price) decides to murder every member who is ahead of him in line to a dukedom. Every member he murders, both male and female, is played by Alec Guinness.

Unusually for the 1940s, it portrays the British ruling class as venal, corrupt and ineffectual. As it happens, Valerie Hobson plays one of the love interests. As the wife of John Profumo, she would later be part of the history that showed there is sadly some truth in this.

Great list and also a reminder that I should restart to watch old movies soon.

It's fantastic to see this article that I didn't know about, and how in the earliest days of Filmsite in the late 1990s, it had such an impact on you. Now I'm about to go into Filmsite's 29th year, and you're right in some respects. I am more interested in past classics from the 20th century, rather than the latest releases. Thanks so much for catching me up on what you've been watching.